01/20/2026

A long-lost medieval green has been revived thanks to SUNY Cortland’s Chemistry Department.

“Iris Green,” a pigment extracted from the petals of blue iris flowers, was popular in the medieval era as an alternative to other, more toxic pigments such as malachite. The distinctive shade appears in many works that have survived to the modern day, especially medieval manuscripts

Those manuscripts were far more vivid than we know them to be today, according to Lynn Schmitt, lecturer in the Chemistry Department.

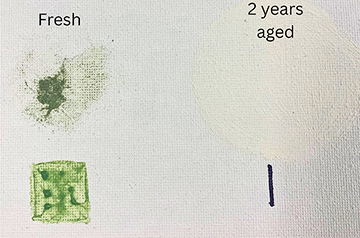

But no one — including art conservators — knows exactly what that shade of green looked like. It’s susceptible to fading to a duller yellow with exposure to light. With the loss of its true hue, the artists’ intent gets lost to centuries of fading.

Without a reliable modern formulation to remake the pigment, the true appearance of many pieces of medieval art was left unknown. This and other “fugitive pigments,” or pigments that fade over time, create an enduring mystery, one that Schmitt was drawn to.

Now, through Schmitt and their students’ work, Iris Green’s formulation is closer to being understood.

While others have looked at this pigment, many have simply mistaken it for other greens, like chlorophyll green that comes from the leaves of plants, rather than from the petals. Others have accused Iris Green of having the same coloring molecule found in sap green, which is derived from the buckthorn berry.

Medieval texts, though, hold the true answers for how to recreate Iris Green even today. It may have taken long hours of trial, error and testing,

“I have a background in medieval studies,” Schmitt said. “I got an accidental minor in it when I kept picking medieval art classes because I thought the art was super cool.”

This incidental degree turned into a real passion project.

“My interests are in translating medieval texts to meaningful chemistry, figuring out the exact ratios or what we call stoichiometry, of each component, what the structure of the actual pigment is, and then what does it fade into and why is it fading and how can we stop it.”

Before joining the faculty at Cortland, Schmitt was a lab coordinator for a federally funded course at Binghamton University called Materials Matter, which focused on the link between art and science. It was there that they first learned about Iris Green.

Schmitt liked the idea of reproducing a pigment from medieval manuscripts for lessons due to its nontoxic properties and affordability. But the pigment was far more interesting and mysterious than originally met the eye. Seeing the pigment fade in real time and not having a clear explanation as to why puzzled Schmitt.

Additionally, traditional ways of studying pigments are not applicable to pigments derived from plants, which creates a challenge for conservators to get proper information about the work they are tasked with preserving.

With more investigation, Schmitt learned that published works sometimes mislabeled the color or were otherwise incorrect.

Once Schmitt was at Cortland, they thought the subject could be a great learning project for their students.

“I saw this pigment and these pigment formulas and texts and was like, ‘There’s some real chemistry going on here.’”

With samples of the original Iris Green recreated from medieval manuscripts, their classes used the spectroscopy resources on campus to begin to solve the fading color puzzle.

“The students take a component of the broader research, and they really work to make it their own and see where it takes them and uncover those facts,” Schmitt said. “It’s absolutely a student endeavor as much as it is advised from me.”

As part of the project, chemistry major Alyssa Reardon ’25 created an historical pigment library using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The new database will make any future research on fugitive colors at Cortland easier.

“At first I was really nervous coming into the project, as I did not know what to expect,” Reardon said. “But Dr. Schmitt broke things down in a way that was understandable and fun for me. By the end of the project, I had finally understood the importance of every step we were taking, making the experience much more interesting and enjoyable for me.”

Reardon is now considering pursuing an online master’s program in environmental engineering through the University of Tennessee, where she was recently accepted.

“I feel that this project pushed me out of my comfort zone with chemistry,” Reardon said.

“I did not have much experience with the FTIR or other instrumentation prior to the project, so I definitely felt confident using instrumentation by the time I graduated college.”

Rebuilding the original Iris Green is just the start, Schmitt added. Next is gathering more data, so that art conservators get the puzzle pieces they need to figure out just how much Iris Green fades given a specific amount of time and conditions. That way, when these centuries-old artworks are retouched, they’ll finally be seen and studied as the artists would have wanted them shown.

“Now it’s in the aging of the pigment, identifying the structural changes that happen that change the color so much,” Schmitt said. “And then identifying the chemical process that’s going on, so that we can apply things like varnishes or other protective layers to the painting after it’s been retouched in a way that’s not disingenuous to the work.”