Buildings as Unsettling Metaphors:

the Constructed Worlds of Gary Sczerbaniewicz

Dr. Jennifer Minner interviewed Gary Sczerbaniewicz as a part of her preparation for her lecture titled "Dark Houses and Eerie Cityscapes," a panel consisting of creative responses to "The Tower and the Shard," Sczerbaniewicz's solo exhibition. The recorded audio file was 1 hour and 53 minutes long. Thus only an edited portion of the interview is published. This conversation took place during the Pandemic of 2020 via Zoom.

JM:

I am intrigued by the way that you explore emotions and unsettling themes in your artwork. I’m coming from the perspective of a professor who teaches city planning and preservation. In these professions we typically choose to ignore the eerie and unexplained. So often it seems that we’re trying to create perfect cities that are completely sanitized. In your artistic practices, you are able to explore and even construct strange, unnerving spaces. What do you think people who build design or regulate our everyday world could learn from your artwork?

GS:

I think some of my own experiences trained me to look very carefully. I was a wayward high school student. Didn't know what I wanted to do. I didn't really enjoy anything except for art. While attending college in pursuit of a degree in Construction Management I took an Art History overview course, which completely opened new doors for me. I also worked as a drafter and model builder for an architect in Utica. Also in the Buffalo area, I worked for an architectural restoration firm—a terracotta restoration company—Boston Valley Terracotta.

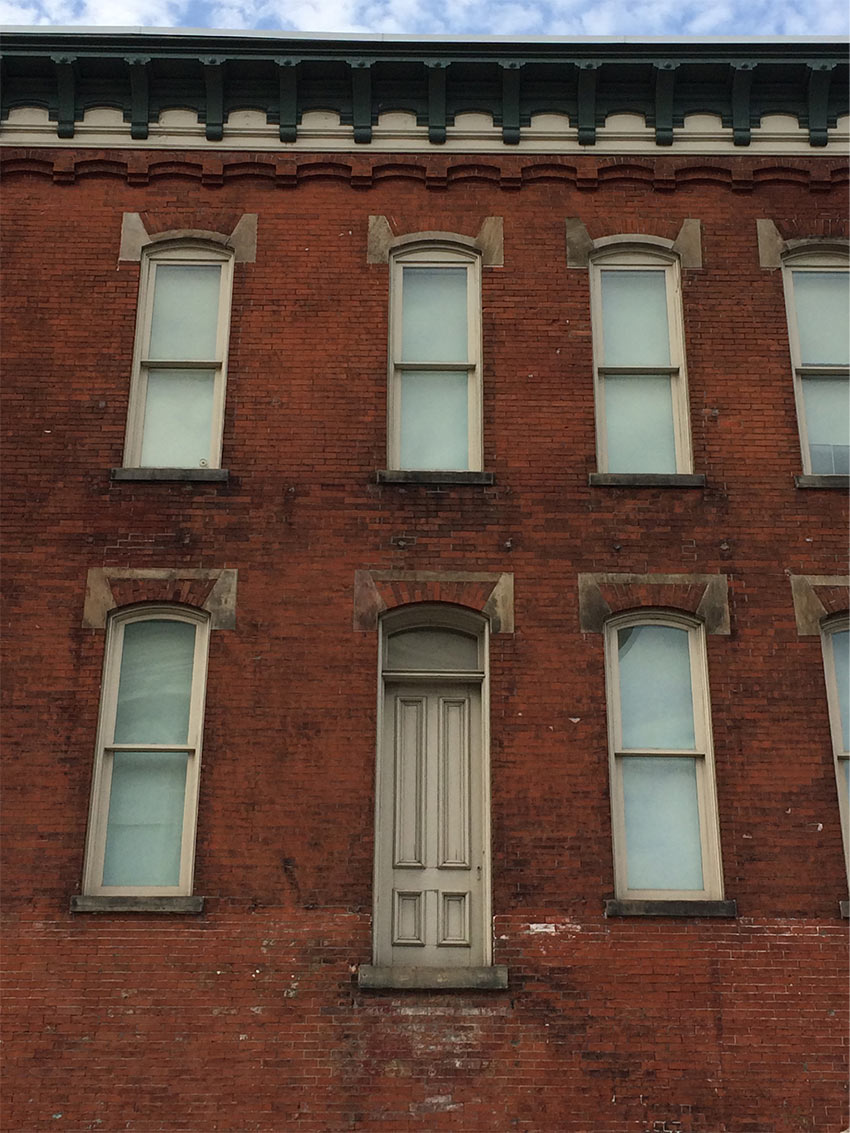

In the process of architectural restoration, especially with the terracotta company, we would go to New York City and conduct in-depth site surveys of the building facades that were identified for restoration. We would estimate and photograph the existing cornices. Then we would mark and remove facade samples to bring back with us for mold-making and drafting purposes. That process trained me to look at buildings, look at evidence of the past, and search for other iterations of those buildings. I started to look at those [modifications to buildings] as signs of economic, either prosperity or decay, right? In terracotta, a cornice that's been ripped off and clad over with aluminum or some other cheap façade material.. that was an obvious sign of the cost of maintaining the building, the cost of maintaining the structure and the hasty cheap, easy capitalistic way to just simply cover it. But certainly city planners and preservation professionals are much more in tune to the value of historic fabric or the architectural layout of the city.

It's the construction managers that you have got to watch out for. It's like naked capitalism. It's all time and money and get this done. I think where my hope lies is in the design and the process where architects and city planners are more sensitive, they tend to be right because they're in tune to the history and the artistic value, and the aesthetic value and the functional value as well. What I think that those career paths can glean from my work... probably just that there are different ways of interpreting the built environment and its iterations. For example in Juhani Pallasmaa's the Eyes of the Skin, thinking of the building as sort of surrogate for the human.

So looking at the face of a building, like looking at a human face, you can see wrinkles, you can see blemishes. You can see where a person is excited by their life and their history or they're downtrodden. Seeing windows that are covered over, maybe through hastily weather tightening the structure, or due to vandalism and encroachments of some unwanted force in complete opposition to the original design intent. To me, that's a sad thing, right? it’s when a building, once designed for full interaction and full experience has been shunted and closed over and denied.

I'm coming from my experience, living in Buffalo, which is a beautiful rust belt city. We've got such a diverse architectural fabric.We're getting more sensitively constructed, contemporary buildings in our city, thanks to energized city planners who are very interested in maintaining the history and not dozing over it, but augmenting it and complementing it. And I think they're doing a great job, but there are those signs of the past, like phantom limbs… like vestiges of a once promising or once vigorous infrastructure that is now just evidence.

Let me show you some examples of what I’m talking about.

GS:

Okay. so can you see the image on my screen?

GS:

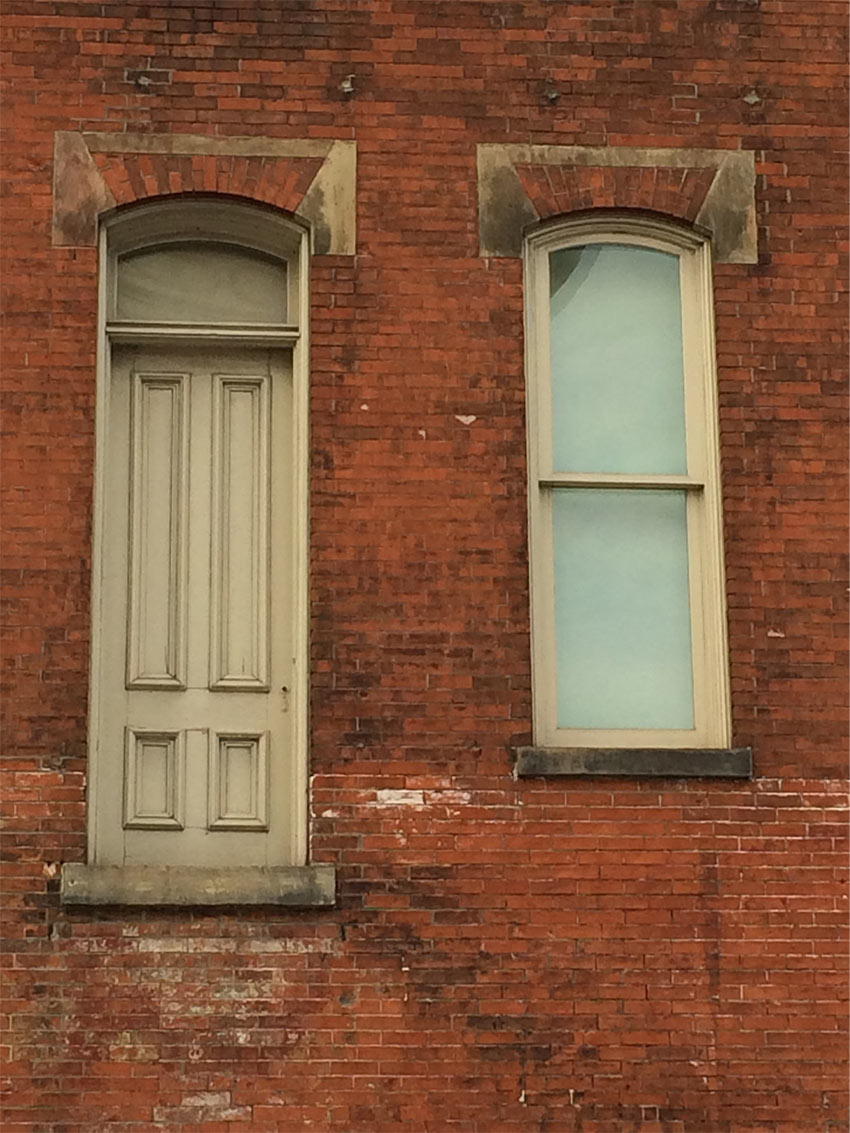

Okay. So you can see this photograph of a facade that I have open in Photoshop. This is across from the Scientology building in Buffalo. And there's this beautiful brick facade with this solitary doorway in the middle of the second floor. It’s probably done for utility or an adjacent, either a covered stairway or an adjacent building was demolished to open up the facade. But again, a door opening onto nothing is a fascinating, again, very simple metaphor, but a handy one.

JM:

That's a fantastic image.

GS:

This is a beautiful building. [Flips to another image.] I love this sort of umbilicus coming out of the facade, terminating into the dumpster. And I've made use of utilitarian demolition chute”coming out of the building as having some sort of metaphorical connection. I mean, I don't think this is something that planners or architects would respond to. But for me, as an artist, this constitutes a beautiful vignette.

If we accept the notion that architecture is akin to the human body, then there's some beauty in extending this analogy to the processes by which foreign bodies are extracted from, and repairs made to both buildings and our bodies. Evidence of these 'surgical operations' is readily visible in many cases and provides ample source for metaphorical exploitation. And then just looking at the facade itself and all the different brick patches and anchors and all of this beautiful language that was once that was once, you know, visible, I think is, is important.

Another image that I have from South Buffalo. This was en route to my studio." with: " The next image was taken in South Buffalo near my former studio. In this example we can see the residual evidence of a demolished stairway. I interpret these traces as a record of vertical locomotion, which can be metaphorically extended to represent psychological or emotional states of elevation and descent.

It facilitates vertical transport of the body from one level to another. And then in many of these cases on the left side,there's a sort of pressure-treated, more contemporary porch deck, which is, you know, maybe not sensitive to the original design.

[Changes images.]

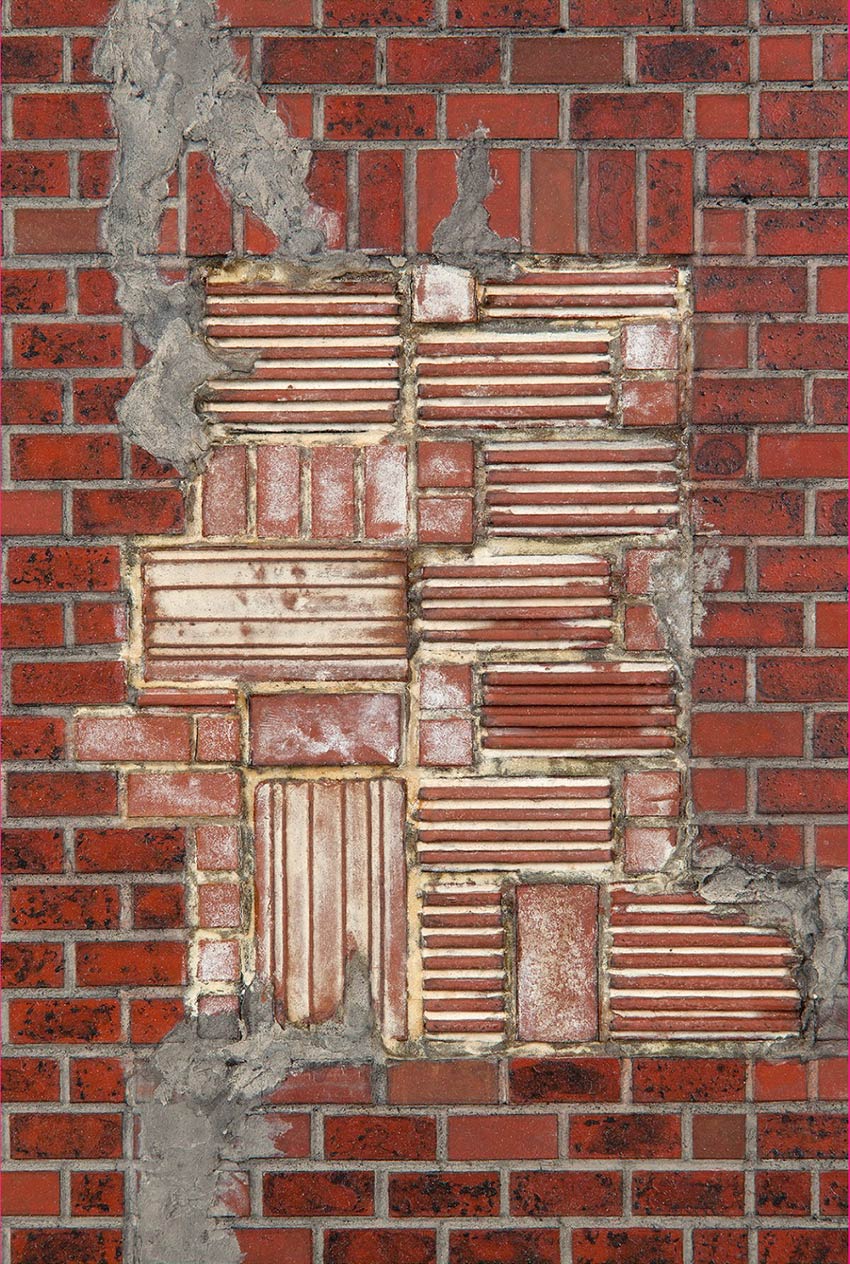

This one is one of my favorites. It was a building near a Tim Hortons drive through in Buffalo. I incorporated it into one of my pieces in the exhibition -

‘LRH Tech'

Detail at Window Infill

Wood, MDF, cast plastic, plaster, ink, acrylic, latex

18 ¼”W x 18 ¼”H x 1 ¼”D

2017

‘LRH Tech'

Wood, MDF, cast plastic, plaster, ink, acrylic, latex

18 ¼”W x 18 ¼”H x 1 ¼”D

2017

It says a bunch of things. First of all, it's beautiful just as a patchwork. I love it as just a sort of masonry quilting of this, this, you know, form follows function kind of thing. It says: "We didn't have the correct, color-matched historic brick, so we filled it with whatever we had at the time."

GS:

There's this janky mix of speed tile and brick, and also beautiful patterning, right? I don't know if you can see it, but if you're counting up from the bottom of the speed tile, every other course has these sort of soldier courses turned. There's an intentionality to the jankiness, which I absolutely love, but it reminds me of this hasty surgery where we don't have the right materials, but we've got to patch it up… we've got to weathertight it, and it says a lot of things. Now they've painted over the whole thing, the facade to blend it all in, but I wish they hadn't because, you know, that shows you, a certain record of a certain time in which perhaps, most likely utility and function were the main question, not the aesthetics, right. And that's a gem of a vignette.

JM:

Is that craft or lack of craft?

GS:

That's just, it, that's a great point. I think it's both. I mean, at least on the right side where the speed dial is configured to the left side, a little bit more janky, but certainly on the right side, there's some level, there's some respectable Mason in the world that ”That’s good." [Laughter.] So I use that as a metaphor for work.

I often use titling in my work to add another layer of concept to the viewing experience. Now the viewer is not going to get all the titles or all the references, and that's totally fine with me. At the time I was researching Scientology. I don't know, I don't want to insult you with you if you are a Scientologist.

JM:

I'm not a Scientologist.

GS:

Many, many smart people are embroiled in what seems to be some sort of pyramid scheme, or it seems to be just a grift basically using pseudo-science fiction, pseudo-religious language… what they call the teachings. The actual scripture in Scientology is “tech” T-E-C-H. And they call it LRH Tech, which refers to L Ron Hubbard. So I titled that piece LRH Tech because it's this janky tapestry of masonry infill. I was researching Scientology at the time and that title just made sense to me. I want the viewer to have an engaged experience, taking in the work. But, you know, there are certain things you do purely for yourself. And one of them is this titling, and I also buried a portrait of L Ron Hubbard in my piece.

My intent was not to reproduce the facades exactly as shown in the photos, or to reference the history of any particular Buffalo landmark." I mostly take inspiration and sort of paraphrase the vignettes that I see in the built world. Here’s another example. I have a piece in the show called Bridge to Total Freedom No. 3: Diminishing Returns. You'll see a facade where there are several different iterations of adjacent or adjoining gable roofs that sort of go down through time till they arrive at the squat structure at the bottom of the piece. And again, it's a sign of a capitalistic trajectory that somehow documents the life of the city.

We see a lot of that in Buffalo. From a visual standpoint, it's quite interesting. but I wonder what it does to the average person. I wonder if the average person takes note of a lot of details like this. I think for me, it took all that, all those lived experiences of counting masonry and looking at the substrata of the buildings, looking at the support systems, looking at the stability of the facades and really careful, careful looking at what is there in order to kind of gain a sensitivity to this. I can't look at a building without immediately trying to trace its history. And even in this image, you can see CMU and fill underneath the door. There's this, you know, calcium leaching under the door, the beautiful tar of the gable roof and the remnants there, the mortar patches, the very strange paint job. It's just metaphorically loaded in my opinion, to psychological analogies and states of thinking again, doors that go nowhere. Blocked windows and the like.

JM:

Is there something about Buffalo that inspires a special way of seeing the city?

GS:

So I grew up in a suburb of Utica in a very 1950s era "ranch house. All the houses are one level, no basement, no attic, very, very basic ranch housing and very, very suburban. And when I moved to Buffalo, it was like, Holy crap. You know, we've got the HH Richardson complex, which has now turned into a high-end hotel. And I thought, initially: “my God, how's that going work?” If there's so much psychological weight of a 19th century institution that it might curse... but no, it's beautiful. They've done a wonderful job, super sensitive to the history and really saving a gem from those utilitarian… those ugly-minded developers who just see space for parking lots.

I think Buffalo now understands the errors of the past. And so it's generated a family of artists, city planners, architects, who all really enjoy the depth and the quality of architectural fabric that we have. Coming from my experience with Boston Valley Terracotta, we would drive along Broadway Street, and note all of the terracotta facades, the polychrome glaze. We would marvel at all the materials involved in that. And hope that someday somebody will say; “Oh, God, we need to save this!” This is a precious part of our history that to demolish it or to build over it or to ignore it would be a crime in a way, right? An aesthetic crime at least, and more than just an aesthetic crime.

JM:

Can you talk a little more about the connections people might have to your work because of the depictions of the built environment?

GS:

I would hope to foster a sense of curiosity for the historic buildings in our midst, and an enhanced form of observation of the myriad details visibly present in these structures. I know this takes time. Which a lot of many people don't have a lot of. However, in the COVID-era, some of us do. And I think the act of looking at our environment is so important. I'm hoping that my extracted vignettes might inspire somebody to be more aware of the fabric of architectural history that exists in their own setting. You know,I think everybody can relate to a door, right? It's a utilitarian, functional means of egress and entry. And we know what that means to go through a door. So, observing an exterior door located on the 2nd story that appears to go nowhere- might seem strange, impractical, or absurd.

We all can relate to the act of looking through a window. And we can recognize trauma in things like deterioration or neglect. These signs of neglect provide artists with ample subject matter from which to draw upon. I'm hoping that these details inspire someone to look a little closer at the makeup of their surroundings. Maybe to ask questions: Why is that like that?”, “Why are those doors and windows blocked?”, “Why does that building look like it’s a mishmash of styles and differing materials?” - “ maybe that could get them somewhere… toward understanding other elements of cities caused by economic hardships or struggles, right?

We all know that maintaining buildings of a certain age with historically accurate materials is really expensive. To convince the purely capitalistic, utilitarian-minded developers and builders of the depth and value of that rich history is no small task. I sometimes think about looking at buildings like a geologist or an archeologist would examine them - recognizing signs of trauma, upheaval, neglect, or revisions made through the ages . You can readily perceive these same signs in the architectural landscape of most older American cities- including Buffalo.

JM:

I really like what you said. It's deeper than just, well, in the parlance of preservation… these are the ‘character defining windows” or these are common architectural styles. What you're talking about is how we maintain the built environment and respond to trauma or entropy in it.. I think that's a really quite special observation and also aim to get people to notice these states and think about how we relate to them.

So can you tell me more about the personal meanings behind the artwork? So there were some things you alluded to in the talk, especially around Catholicism, but there was a limited amount of time. Would you want to share anything else about that?

GS:

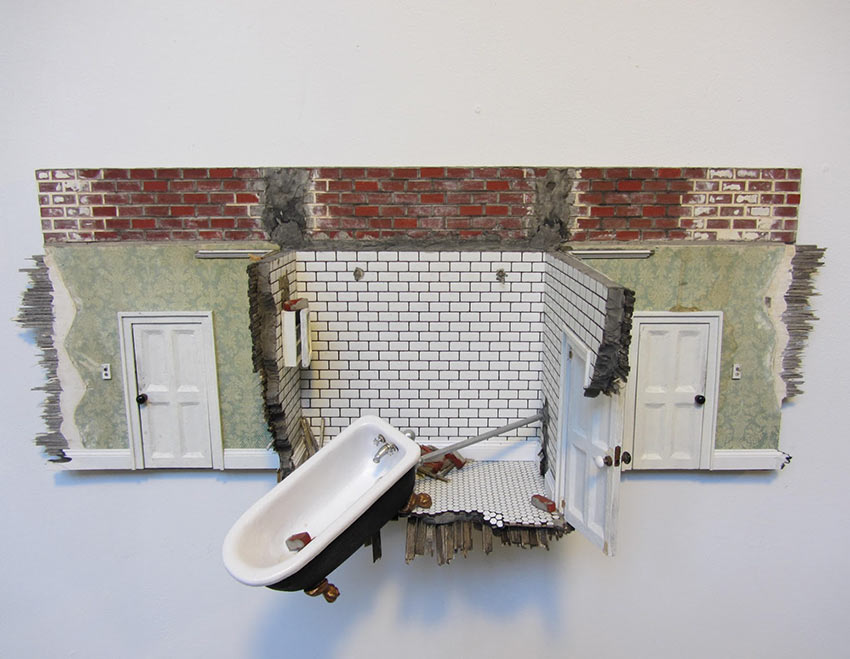

So, I went to a Catholic church and I attended Catholic elementary school at a place called Holy Trinity church in Utica, New York. Inhabiting that dimly-lit neo-gothic church space always yielded a mixture of emotions and psychological reactions in me ranging from the sublime (mystery and wonder), to the darker aspects of guilt, fear, and shame. When I was younger and didn't understand the language (masses included a mixture of English, Latin, Polish) and ritual of the mass - I would engage in active daydreaming. In that pursuit I would study the various mystifying architectural details: massive cluster columns, mosaic tile patterns, stained glass windows, vaulted ceilings - with their night-sky patterns (akin to those seen in ancient Egyptian tombs), zones of deep shadow, various paintings and statuary- all contributing to a pervasive sense of dread.

I think about those zones of deep shadow as refuges for the imagination. There were also sub-architectures within the church itself - chapels, confessional booths, choir balcony, and various little niches where statuary were displayed. I really loved fantasizing about those little nooks as sort of compartments that you could inhabit and hide in. . At that time I was indelibly impressed with the association of the body to ritual within the Catholic process. At various times during the Catholic Mass you're standing, sitting, kneeling, and maybe other iterations of those postures. And the architecture is laid out to facilitate that ritual process. I found that I could play with that personal experience by creating my own ritual process within my installation works where I could create a viewing scenario to reveal something that I want to communicate.

In my experience with the church, it would be... you go to this church, you perform these ritual body movements and you say these incantations and magic happens. And some kinds of weird stuff happens, but in that space itself, but then I walk out into the daylight and it disperses. Maybe parts of it are there with me lingering in my head, but the power of it kind of disperses, which means that that architectural space is the site of a very specific form of communication. I have attempted to infuse that ritual experience within my installations. I'm trying to communicate something to you very specifically, but it only makes sense - and it only exists - under certain prescribed parameters- for you to kneel, for you to sit on a cart and pull yourself into it, or for you to lean or stand in a certain way. These viewing postures contribute to the overall conceptual layering and framework of the installation.

That's part of what I absorbed from that whole Catholic experience. As a long-time ex-Catholic, I still find it's the creative gift that keeps on giving- and I love that lineage. It goes back in time to such a rich history. To Roman history... because it inspired so much of art history, it seems like a very firm foundation to kind of play with and to exploit and to reference in some of my small sculptures such as ‘Nihil Obstat.’

‘Nihil Obstat’

Wood, cast plastic, chipboard, acrylic, MDF, plaster, ink

24”W x 14”H x 6”D

2016

Private Collection

There is this deteriorated house section where I bring in some of the Catholic language. For me, that's a way to nod back to that history and to refer to a psychological equivalent of what the visual is communicating and through the very specific language of Catholicism in that history.

I also grew up, in that same suburban area (Central NYS) in the late seventies and early eighties when the cold war was waning. We lived near Griffiss Air Force Base, and we had constant overflights of B 52 bombers in the area. To me, it was the most sublime experience seeing this massive piece of metal keeping itself a float in the air, hovering over the Mohawk valley - not knowing at the time that these were SAC (Strategic Air Command) bombers and they were armed with nukes.... I think it all goes back to our initial comments about childhood memory and about the stuff that made such an indelible impression on me in those formative years of sublime wonder, but also tinged with its gray clouds of guilt and shame and all that stuff.

There was always that coexistence of sunlight and darkness in my childhood memories akin to that which we often see in David Lynch's films. He's got a brilliant sense of juxtaposing bright-white innocence with deep-dark evil, and keeping them somehow radiating in the same space. In my work there are ways of responding to what I currently see and experience, but also in leaning back into my own history and exploiting those or applying them to create meaning.

JM:

So next, I want us to talk about the ways in which people miniaturize the world and why they do it. I mean, this is something that fascinated me in your work. I think about miniatures and models as sort of aides for fantasizing about the past or creating a future. They are about playing with places or gaining power over worlds and constructing them. So could you talk a little bit more about miniaturization and model building and how to understand that in your work?

GS:

That's a great question and I love the examples you give. I think I agree with a lot of those examples -- about what model making and miniaturizing implies. For me it was two things: first, I loved doing it as a kid - building dioramas for science fairs. I knew I wasn't good at a lot of technical aspects like making things move or making a volcano explode or building with erector sets. I loved this sort of compartmentalized, unlimited world-building that could happen in dioramas. Going to natural history museums and seeing the scale models, even though you knew they were facsimile, they somehow transported you more than just text on a wall or a photograph or a drawing. They three-dimensionalized the experience and allowed you to ponder the nature of what you're being shown.

Secondly, before attending grad school I had done installation works- where I would seek to fill a space with large quantities of a certain material. And that became very exhausting, both financially and physically. At that time I had a eureka moment... I initially received a tiny studio at University of Buffalo whenI began graduate studies. I realized I could go the other way… instead of going literally mad trying to fill spaces with material, like some of my hero artists - like Ann Hamilton and Robert Wilson- who do massive, epic installations that trigger the sublime experience. I realized that I could evoke that sense of epic scale through an alternate means- by constructing small-scale worlds placed within a mid-sized architectural sculpture that could be accessed by the viewer as they adopt some atypical body posture. This mode could approximate that same kind of expansive experience that the larger works sought to produce. My current work Neil Before Zod is an embodiment of that intent as is currently on view at the Dowd Gallery.

My initial process includes working between sketchbook schematic designs and scale cardboard models to arrive at a viable form and concept. I enjoy the freedom and artistic play that occurs during this nascent phase of a project - as it often dissipates once a design is committed to. Here- scale modeling plays a dual role both in envisioning a complete installation and by viewing its constituent components.

As an aside- one of my favorite recent films - Ari Aster’s’ Hereditary’ uses scale models as part of the main character’s profession and also as a narrative/ world- building device; it’s a very dark film but extremely effective at creating an terrifying psychological mood using architectural miniatures. I don’t know if you’ve seen it but I highly recommend it.

JM:

[Laughs] Yes! The film is so haunting!

GS:

In it, (Hereditary) she's working on scale models, which then become her way of coping -processing the unfathomable traumas she is beset with. So I think that use of dioramas can be a surrogate experience for a certain type of simulation -- simulacra that I'm interested in promoting or communicating to the viewer.

When I went into my undergrad at Alfred, I came in as an object maker. I then learned about performance art and video art and things like installation. And I loved the ephemerality of it all, but now I've gotten back to my love of object making, and it really is a challenge. You know, I do a lot of the model building, with my own designs and in my own scales and I'll use a model part here and there, but it's 99% of my own build. There's something sort of meditative or contemplative in losing yourself within the miniature, and in the crafting of the materials- right?

Another film reference - incidentally included in the Dowd Gallery exhibition programming is Jan Svenkmajer’s ‘Alice’. I first saw this Czech New-Wave gem during my undergrad studies at Alfred University and it made a huge impact on me as an artist. Not only does the film’s protagonist undergo a series of surreal and absurd scale changes- often using models and miniature elements as setting or objects- but there is a gorgeous approach to conveying extreme materiality throughout the narrative. This produces an almost hypnotic effect of saturation within both a psychological and a physical, highly tactile world/space.

JM:

I also want to ask you to talk a bit more about how you ask people to engage both physically and mentally with your artwork.

GS:

I believe that there are certain encoded or specific messages/concepts that require an equally specific means of delivery. It’s almost like that colloquial phrase: “You’d better sit down for this.” - implying that the weight and potential impact of the message could alter or disorient the recipient.

In a lighter sense- I think of it as analogous to the experience of hiking along a marked trail, right? If you go, like I spent a lot of time in the Adirondacks as a kid. I miss it terribly. I haven't been there in a while, but when I'm going on a hiking trail there are usually prescriptions in the trail that lead you to some vantage point, right? And that vantage is more than likely some sort of sublime vista that transports your spirit or your mind to the wonder of the environment. But going along that path, you can turn around at any point in that path and not see that prescriptive thing, or you can see the things on the left and right of the path or above and below. You can see anything that you want along that trail. But in order to get to the vantage that it's designed for, you've got to agree to follow its route to that conclusion.

And so there's a little bit of that invitation here in my work. If the viewer accepts the path that I've marked out, then there's a promise of something at the end of that path that hopefully will clarify and justify the journey and the energy expenditure.

JM:

Before encountering your work I hadn't really considered church spaces, for instance that there is built-in furniture - in every pew that makes routine the encounters with the unseen. And so ultimately, what does this sort of furniture for, you know, encounters with spirituality? What does it say about humanity?

GS:

It could be like the hero's quest, right? During the Catholic Mass the body is in constant positional movement corresponding to certain portions of the scripture. This bodily subservience to ritual is both a slight physical discomfort and a sign of the participant’s level of reverence for the material to be disclosed. These mild bodily exertions (standing, sitting, kneeling, genuflecting, etc.) are perhaps some part of the religious concept of subjugating the body to the aims of the spirit. It's, I mean, it's like, and going and doing that repetitively creates this sort of hard-wired loop in your head that programs you to such things...

The first time I went to Egypt...I went by myself and part of the trip was going to Mount Sinai. And on the site is a Coptic Orthodox church. I stayed in a hostel located at the site of this church. There- the men had to sleep apart from the women. And in the morning there was a ritual procession to the apex of Mount Sinai to see the sunrise. It started at four o'clock in the morning and it was a candle lit procession that wound up the hillside into the mount to experience the summit. In the procession, there was this throng of supplicants or worshipers that were crawling on her hands and knees- supine all the way up to Mount Sinai. I was like, “Oh my God!”, this is mind-blowing. So, indeed I am ‘hard-wired’ to both procession and ritual.

JM

I think you're right. People want that struggle. There is a physicality to this struggle and mental endurance that they want… you could even relate the desire for struggle to Q-Anon and other conspiracy theories. It's like some people really want to believe that they are in an epic struggle - almost a compulsion that plays out in their minds for some reason.

GS:

Yeah. It's terrifying. It's an alternate universe, but it's also fascinating. I mean, you think about things like Freemasonry, where there are degrees of masonry, and there are degrees of access to the benefits of masonry by enduring such and such travails. And there are physical processes involved in that. Scientology has real scammy, weird stuff like that, where procession through some type of pain promises a reward in the future. You know the dark ends of that are Jim Jones and like Guyana, right.

I think it's just a fascinating trough or artistic toy box to play with - belief and non-belief. I'm not even trying to convince anybody to believe something. I'm trying to communicate that often when confronted with a revelation of some odd sort- there is this sense of disorientation that happens as we try to marry this new data with our previously held ontologies - often compelling us to compartmentalize the new data- cordoning it off in a sense-until it can be properly addressed. I am drawn to this liminal space of psychological and physical disorientation.

JM:

Is there a risk though that people will sort of take your artwork as depicting something, a truth that is about the conspiracy theory it represents?

GS:

That's a good question., I hope not. I hope that they understand that the way this is playing out is through an art piece that invites possibility and multiplicity of views. But not that I am expecting you to supplant this fabricated simulacrum of reality as your reality. I don't think, for example, if you go to see a movie that's very convincing that you will emerge with the sense that you have somehow experienced ‘reality’. My objective in what I call my ‘special research’ (which involves numerous aspects of Fortean, fringe, paranormal, or Ufological subjects) is to ferret out the crazies and the lunatics from the people who have really tried to seriously scientifically or theoretically figure out what's going on. And so that limits the field down a great deal- to perhaps more respectable sources and people who are actually challenging. I think it's important to make that distinction- even for the eventual sake of generating artistic creations.

I think for art as a general rule, we do challenge the prevailing realities - not to create a counter reality that that inspires violence or harm - but a counter reality that perhaps posits other possibilities.I think an artwork, like an installation or a sculpture can be perceived on a similar level as a film or a novel or a theatrical work. You know, something that is clearly fabricated to express a specific thing, but not necessarily to convince you of that thing. My intent is to play with pop cultural references, to play with things that are floating out there in the ether of our culture, and to draw those together into some coherent disorienting vision.

JM:

Is there anything else that we haven't really covered that you'd want people to really know about your artistic practices and work?

GS:

[Regarding disorientation] We’ve convinced ourselves that we are firmly placed, that our built environment is especially stable, but in fact we are living on a shifting tectonics of continents constantly in motion, riding on a sea of magma on a planet that is hurtling around a star system that’s moving , in a galaxy and a universe which is both expanding and contracting- depending on the expert source. There are levels upon levels of disorienting experiences within our sensory perception. We- as humans try to stabilize and make sense of a few of them so that we can exist and ‘get through the day’. So I think there's a lot that we compartmentalize that we, and we put in a place so that we may maintain our illusion of permanence.

Dr. Jennifer Minner is an Associate Professor in City and Regional Planning within Cornell University's College of Architecture, Art and Planning. For the "Tower and the Shard" exhibition program, she presented the response, "The City As Built is an Emotional Sculpture," for a panel discussion titled "Dark Houses and Eerie Cityscapes: Creative Responses to the Constructed Worlds of Gary Sczerbaniewicz."