News Detail

03/28/2013

The American chestnut was once the most abundant and economically important tree species in the eastern forests of North America.

But then a fungal pathogen was brought over from Asia and has caused the blight, and near extinction, of the Castanea dentataspecies.

Two forestry researchers from the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF) will discuss their efforts to re-establish the tree on Monday, April 8, at SUNY Cortland.

The academics will discuss “The 100 Year Old Battle to Save the American Chestnut” in two separate events that day.

Charles Maynard, a forestry professor at ESF, will speak to conservation and environmental science students at 4:25 p.m. in Van Hoesen Hall.

William Powell, director of the Council of Biotechnology in Forestry, will talk at 7:30 p.m. in Sperry Center, Room 106. The evening discussion is free and open to the public.

The speakers were invited by the College’s Biology Club to give their presentation as part of Sustainability Month and National Arbor Day. The lectures are sponsored by the Biology Club and the Campus Artist and Lecture Series.

Since the discovery of the pathogen in 1904, three generations of scientists and public leaders have sought to find a blight-resistant gene so that the tree could flourish once again in North American forests.

|

| William Powell, director of the Council of Biotechnology in Forestry, makes a point about a young American chestnut specimen. |

Maynard and Powell, with the support of the American Chestnut Foundation, are among those working on methods to generate healthy specimens of the American chestnut tree.

The two researchers began working with the American chestnut tree separately and in 1989 became collaborators. Powell focuses on which gene is the best for fighting the pathogen while Maynard mostly works with the tissue culture of trees, discovering methods of introducing the genes into the tree and attempting to succeed in their regeneration.

“Blight enters the tree through a wound and colonizes it,” according to Powell. “After about three or four weeks, the pathogen morphs and produces a lot of acids into healthy tissue, causing a canker. This eventually cuts off the circulation in the stem and causes the stem to die.

“The canker makes its way and spreads through the whole tree, and in time, kills it,” Powell said. “However, because of all of the microbes in the soil in the ground, the fungus cannot kill the roots.

“The tree can re-grow for about nine or 10 years but then gets tall enough for the blight to attack again, causing a vicious cycle. After some time, the roots lose all of their energy and die off too.”

Today, because of the blight, the American chestnut is what Maynard calls “functionally extinct,” meaning the species is “still kicking around, but is not actually in its natural environment.”

Many of the present-day chestnut trees are grown in blight-free zones, which are mostly greenhouses. However, there is no guarantee that the trees will not contract the blight later in life, according to an article by the American Chestnut Cooperator’s Foundation.

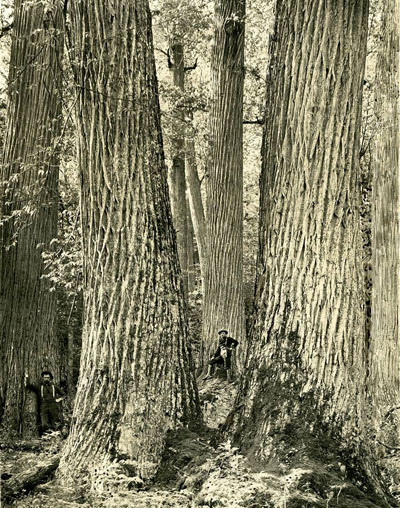

|

| The enormous size, beauty and majesty of the full-grown American chestnut tree is preserved in historical images such as this one. |

According to Powell, there used to be about three to five billion chestnut trees but now there are only about one million of them. Maynard believes it will take another 100 years to reestablish the species.

“The American chestnut was considered a keystone species in the eastern forest,” he said. “The trees that have replaced the chestnut have been mostly oaks, but their nut crop is not as nutritious or consistent as the American chestnut because of weather.

“This affects the wildlife — black bears, deer, wild turkeys and blue jays — that rely on the nut crop to fatten up for winter and survive.”

Unlike many other hardwood species, the American chestnut also produced edible nuts — the chestnut — famously known for “roasting over an open fire” in Torme and Wells’ “The Christmas Song.”

Once used for its rot-resistant quality, the American chestnut was also one of the most preferred timbers for lumber and building.

“More importantly, the pores in the wood are sealed up and are impermeable to water,” Powell said.

The American chestnut is also a sign of heritage. Nicknamed the “heritage tree,” the name chestnut adorns street signs and some town names all over the country.

Their efforts to make the blight resistant genes have taken Powell and Maynard as far as Asia. Researchers there have discovered that detoxifying the acid of blight may stop the spreading of the pathogen throughout the whole tree.

Here in North America, more than 500 genetically modified trees have been planted in carefully selected and fenced research test sites near the cities of Buffalo, Syracuse and Watertown. The planting of these trees is an on-going process.

Before being planted, each tree undergoes detailed surveillance and meets very careful regulations by the United States Department of Agriculture, said Maynard.

For more information, contact Biology Club faculty advisor Steven Broyles at 607-753-2901.