Bulletin News

06/06/2017

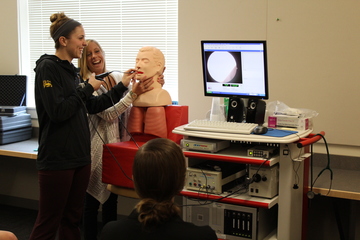

SUNY Cortland speech and hearing science graduate students in Eileen Gilroy’s Instrumentation course recently met their new classmate, Seymour Bolus.

Bolus is quiet. He’s patient. He’s a big, inanimate hunk of plastic and rubber.

He was also the star of the show.

Gilroy’s students came up with the nickname for their new mannequin head that has helped them learn how to practice passing an endoscope trans-nasally. The endoscope has a camera at the end connected to a monitor that shows a live video feed of a patient’s vocal chords, which is useful for health professionals looking to identify speech or swallowing problems.

The nickname is a play on words. Bolus is the technical term for the ball-like mixture of food and saliva formed during chewing. And Seymour? Well, you get the rest.

Previously, students in SHS 643 had practiced passing an endoscope through perfectly straight pool noodles. Gilroy had used a hot glue gun to affix marbles and other small objects along the path, simulating parts of the body the students would expect to see. Surprisingly, that’s not an unusual approach.

The use of a mannequin head for training in the classroom isn’t something most graduate programs offer. That type of hands-on practice typically happens in a hospital or doctor’s office.

“We can’t scope real people because we’re training and there are all sorts of things that can go wrong,” Gilroy said. “We want to use this equipment to help our grad students when they go to their medical placements to work with hospital speech-language pathologists and be able to set this up and know what it is and to know how hard and challenging it is.”

Much of the equipment used by students in the Communications Disorders and Sciences Department is thanks to a gift from alumna Patricia A. Boscamp-Cluss '79. A swallowing lab in the Professional Studies Building is named after Boscamp-Cluss.

Communications Disorders and Sciences Department first-year graduate student Ashley Chanatry, who earned a bachelor’s degree in speech-language pathology and audiology from Ithaca College in 2015, practiced passing the endoscope through the mannequin’s nose. Her classmates looked on — and cheered on — with their eyes glued to a monitor that showed Chanatry’s progress inserting the endoscope through the nasal passage.

“You can do it. You can do this!” one of them yelled.

“You sit there in class and you learn about it and you watch the videos and you talk about how your professors are trained, but to actually do it, you understand how difficult it really is and the different aspects of it,” Chanatry said. “It’s nice to get the practice of it and it’s fun to learn.”

|

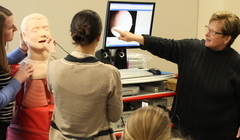

| Gilroy, right, instructs students during class. |

Chanatry may not have to use an endoscope once she enters the working world as her career goals are in a different field. Still, she was glad to get this experience as a graduate student.

“I want to work with kids and specifically kids with autism,” she said. “A lot of people are really interested in the medical field and this is beneficial.”

Gilroy is able to dial up different settings on the training system to simulate different scenarios. That gives the students even more opportunities to learn.

“It’s rare that a graduate program has this piece of equipment,” Gilroy said. “It has all types of functions. It has a function you can put on a little bulb and measure the strength of the tongue. It has an EMG (electromyography) component where you can measure muscle tension.”

As student after student took turns trying to locate the vocal folds on the mannequin for the first time, Gilroy shared plenty of tips and information. She mentioned the correct posture to hold the endoscope, the importance of sterilization techniques and situations in which local anesthetic may or may not be used.

The latest in endoscope technology is a good thing for both patients and medical professionals. The ability to get exact measurements and observations is significant for patients suffering from speech or swallowing problems. This way, their progress may be measured over time.

“It takes the art of what we do and it makes it a science,” Gilroy said. “It gives us numbers and it gives us values and it gives the patient or the client numbers and values to shoot for. It objectifies everything. It’s not just that you’re saying it sounds like you have less tension or you’re swallowing great, you can actually say you’re doing that the right way or you’re doing exactly what we want you to do.”